A castle in the Al-Gharb as a symbol of power change

On the road between Carvoeiro and Lagoa in the Algarve drivers are greeted by a sight that is simultaneously familiar and bewildering. On top of a hill, a pinkish Moorish castle is clearly visible. That is to say, there’s a building whose design and position clearly refers to such a castle. Closer inspection reveals it to be a holiday resort, the Aldeia do Poeta or “poet’s village”.

But that mock castle exploits a powerful image. The Moors[1]Historical use of the term “Moors” is admittedly complicated. Initially referring to Maghrebine Berbers, it was later used to describe Arabs and Arabized Iberians, and really any evidently … Continue reading, a people from North Africa, conquered the Iberian Peninsula in the eighth century CE, and lost their final foothold in 1492. That is still a long rule though, and their legacy is visible until this day. Many geographical names still refer to an Arabic origin, the Al-Gharb (Algarve) or “South Land” of Portugal being the most obvious.

But the Moors also left their mark on the medieval architecture of Portugal. They were ousted from the North of the country over the twelfth century, but held on to its south for a century longer, until 1249. As a consequence, the Roman and (early) Gothic traditions that dominated much of European architecture, particularly “official” architecture, for most of the middle ages bypassed Portugal almost entirely. Instead, when Christianity gradually drove the Islamic powers from the peninsula they took over and adapted what was already there: mosques were turned into churches, and castles proved just as useful to Christians as they had been to Muslims.

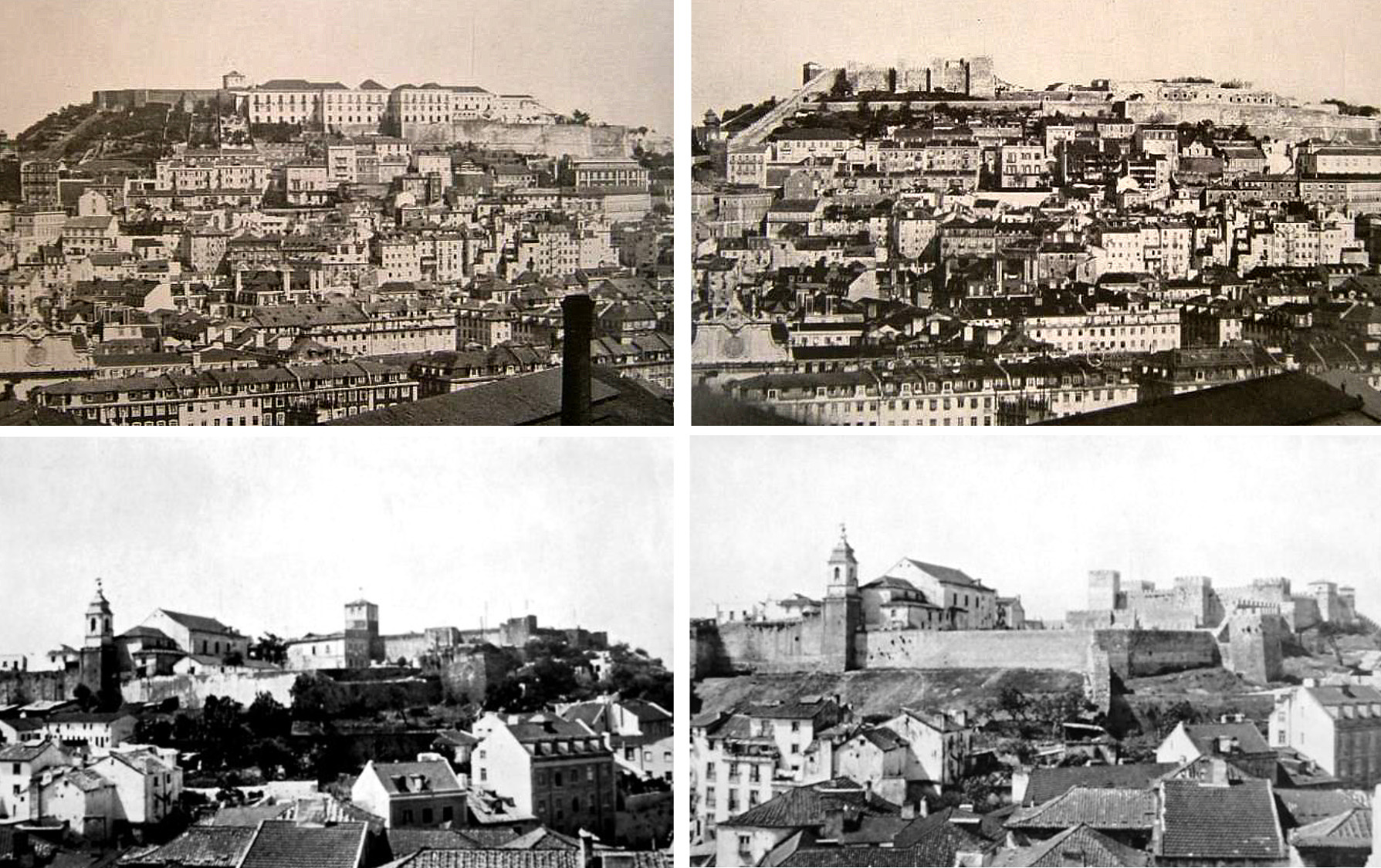

The Moors, of course, knew where to build their castles: they were typically constructed on hillsides overlooking the surrounding area. The largest of them, in Sintra, is of an impressive size and offers a view of much of the area east of the city. But the most famous of all of Portugal’s castles is situated in Lisbon.

But while looking like most people’s idea of a medieval castle, it’s mostly relatively new. Of course, the castle had been there for centuries. Although originating in the first century CE and built by the Romans, had been repurposed by the Moors and Christians afterwards. However, it fell into disuse after the earthquake of 1755 caused extensive damage. While the original structure was never entirely removed (unlike some think), over the years it pretty much vanished from view. By the 1930s, most of it had disappeared under all manners of extensions, annexes, and other things built on top.

Enter António de Oliveira Salazar, the intiator and predominant leader of the Estado Novo, Portugal’s autocratic government between 1930 and 1974.[2]The timeline of the Estado Novo is a bit messy; military dictatorship began in 1926, Salazar became prime minister in 1930, but the “new regime” wasn’t officially introduced until … Continue reading As part of the celebrations around the tercentennial of Portugal’s independence of the Spanish in 1941, Salazar decided that it would be a good idea to restore these old castles to their former splendor. But much like, for instance, Eugene Viollet-le-Duc’s “improvement” of French cathedrals, they ended up as a replica of what those in power thought such a castle ought to look like.

Using the earlier restoration of the huge castle at Sintra as a template, the Estado Novo régime created today’s cranulated specimen from the rubble of its predecessor. While it’s not entirely fake, it is clearly not entirely original either.

But perhaps most ironically, it’s anything but a fitting symbol of the unified, catholic Portugal the dictatorial regime was so eager to celebrate. These castles were typically structures that were used by various ruling cultures in Portugal, and therefore they rather symbolize the plurality of Portuguese history that Salazar et al. sought to forget or at least downplay. If anything, the restorations made them less typically Portuguese.

A smaller castle than those in either Lisbon or Sintra is located in Silves, a few kilometres north of the mock castle this story started with. Like both of its sisters in Lisbon and Sintra, it was given a new varnish of “authenticity” in the 1940s and then the 1960s. Built by the Moors that clung to their last bit of Portugal (Silves was their capital at the time), it epitomizes the changing fate of ruling elites, including Salazar’s own.

You could say that the holiday castle near Lagoa is therefore also a symbol of the Algarve’s new rulers: the tourists that, for better or for worse, have now become the true overlords of the Algarve.

References

| ↑1 | Historical use of the term “Moors” is admittedly complicated. Initially referring to Maghrebine Berbers, it was later used to describe Arabs and Arabized Iberians, and really any evidently exo-European muslim. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The timeline of the Estado Novo is a bit messy; military dictatorship began in 1926, Salazar became prime minister in 1930, but the “new regime” wasn’t officially introduced until 1936. Still, it’s fair to say that as a political movement, Estado Novo got retconned to conform to what was already in place before, with some contemporary (corporatist) trimmings. |